- Covid is having one huge positive impact if governments seize it.

- In its results Roche said of diagnostics equipment – “we are installing in one year what we have installed the prior five years. So we are more than doubling our installed base out there of the systems.“

- This huge increase in capacity, they go on to say, could be used to detect HPV (saving 300,000 women’s lives who die of cervical cancer every year), HepC (helping 80 million people who live with this disease), and Tuberculosis (“one-fifth of population has infection of the bacteria of tuberculosis worldwide”).

- “We need to start to recognize what health care systems can do by intervening much earlier. And I have to say, there is such an opportunity and governments need to get going on this. I’m sorry to get a bit emotional on this, but I have been fighting for 10 years with governments to include HPV screening and all the clinical data is out there, and they need to get going, and not just you know let it go, like they have in the past.“

Author: Snippet.Finance

Inflation Pressures pt 2

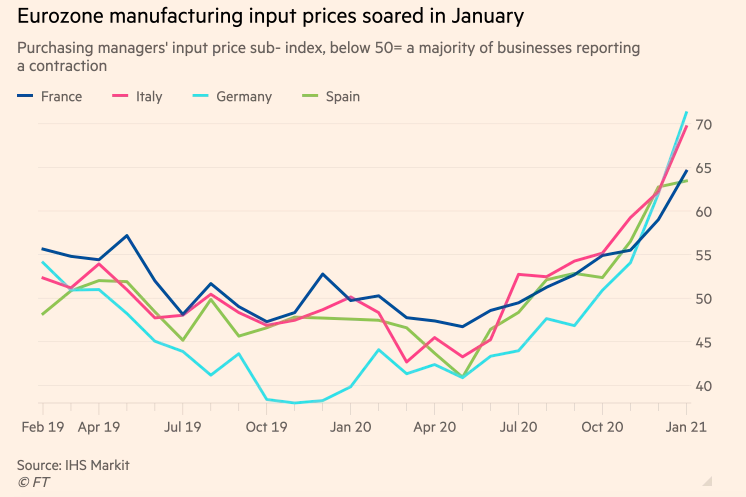

- Purchasing manager surveys of producer prices in Europe are surging (Source).

Inflationary Pressures

- Some quotes on the topic courtesy of The Transcript.

- “…we do expect some significant cost inflation in the year…The top two inflation drivers for this year are expected to be pulp and polymer based materials. Together those two input costs represent more than half of the inflation outlook.” – Kimberly-Clark (KMB) CFO Maria Henry

- “We expect prices to be positive based on all the inflation that we are seeing.” – 3M (MMM) CFO Monish Patolawala

- “…the transportation market is very tight. Spot market rates have increased by more than 30%…And just a bit more color on commodities…we see headwinds on our major commodities right now. But not only on our major commodities, but some of the smaller purchases of raw and packing materials that we use across the rest of our business.” – Church & Dwight (CHD) EVP-Global Operations Rick Spann

- “…we are starting to see a little bit of inflationary pressure, particularly around freight and a little bit in the supply chain as well.” – Danaher (DHR) CFO Matt McGrew

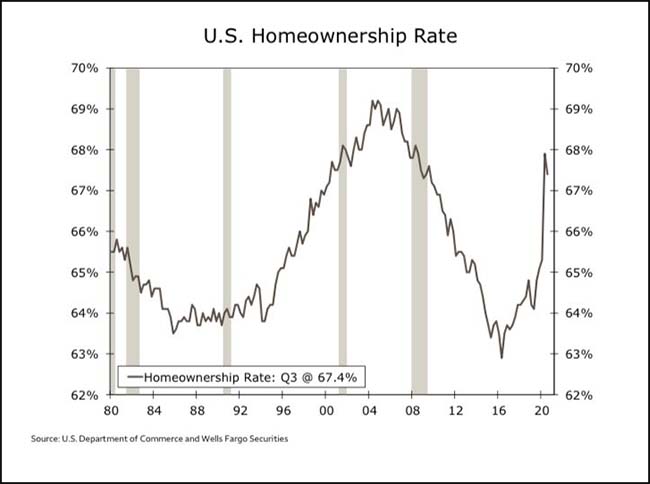

Homeownership Rate

- The US Homeownership rate spike has been remarkable.

- h/t 361 Capital.

Hardware is Hard

- An interesting read on why life is hard for hardware start-ups – primarily the high upfront costs.

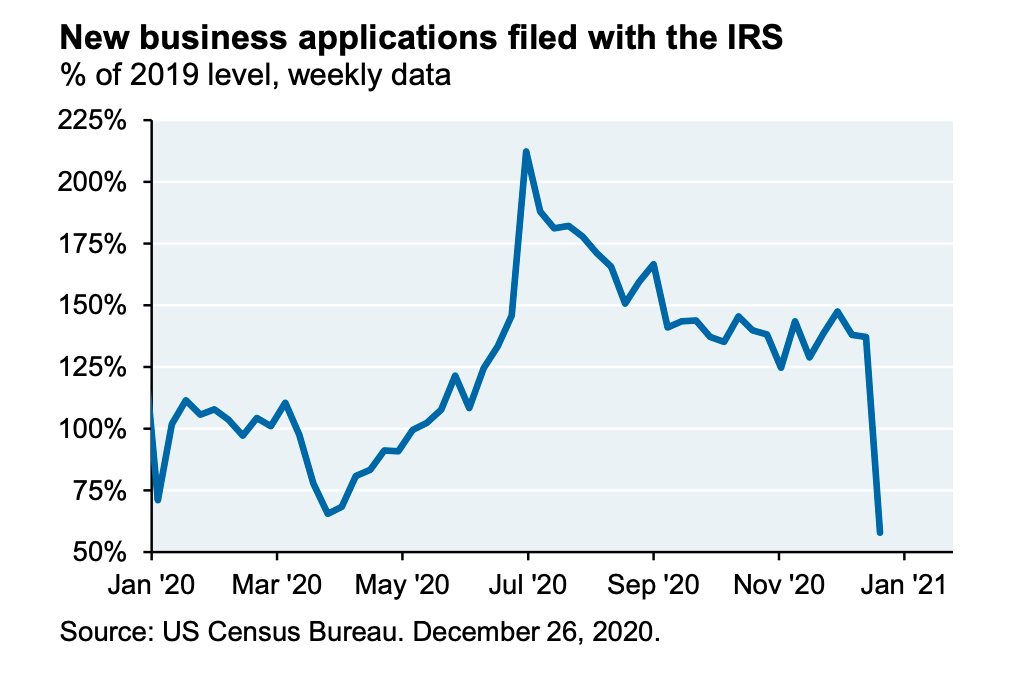

New Business Applications

- New business applications vs. 2019 level has fallen right back.

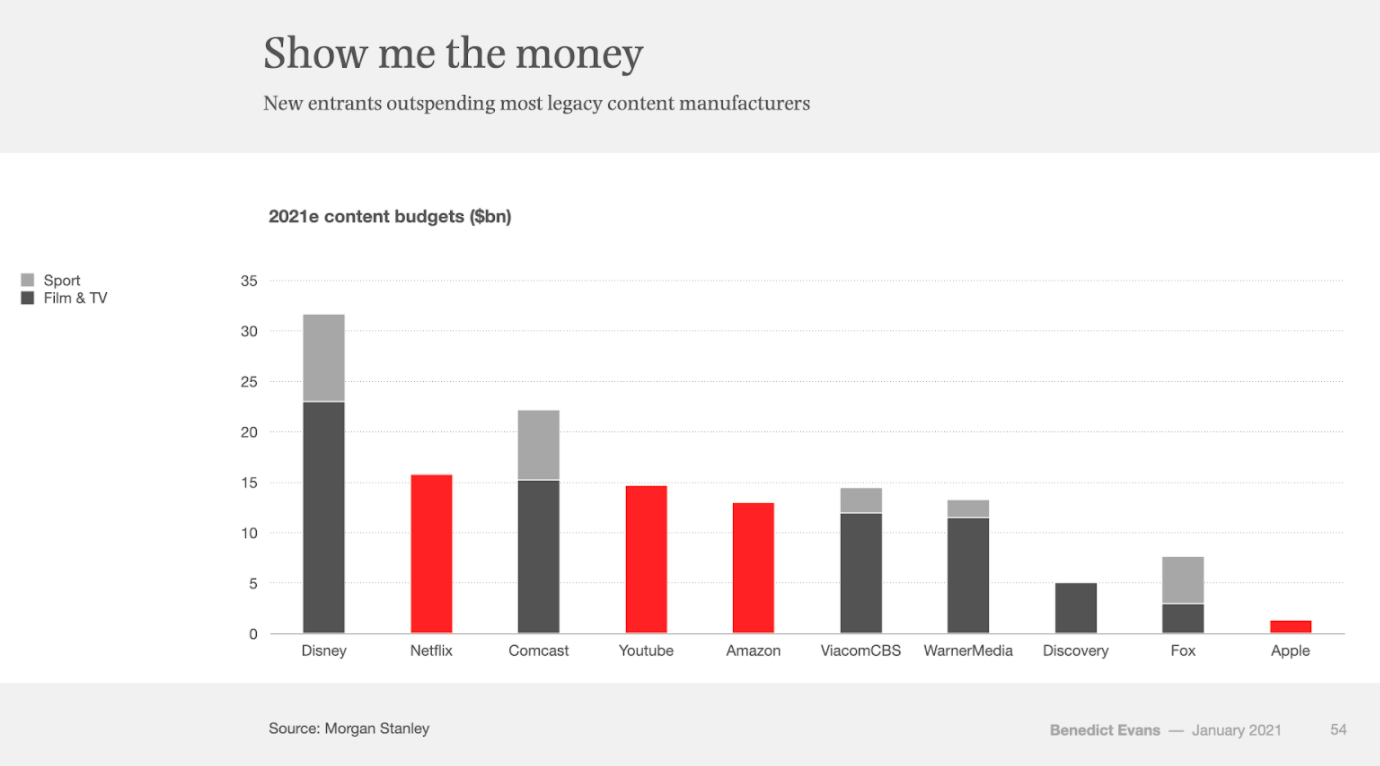

Content Budgets

- The new entrants in media are outspending many incumbents (though not Disney).

- Source.

ARK Invest Big Ideas Slides

- Big slide deck about the biggest areas of innovation.

- A lot of lofty growth predictions but interesting charts throughout.

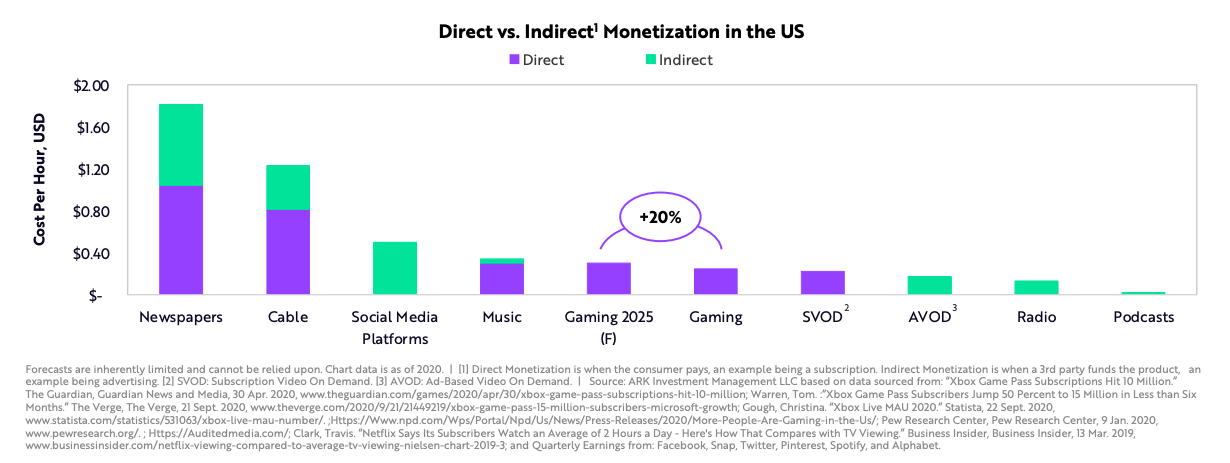

- This one graphs monetisation of various media.

- They argue that even a 20% increase in cost per hour for gaming still leaves it a bargain.

JPM Recovery Tracking

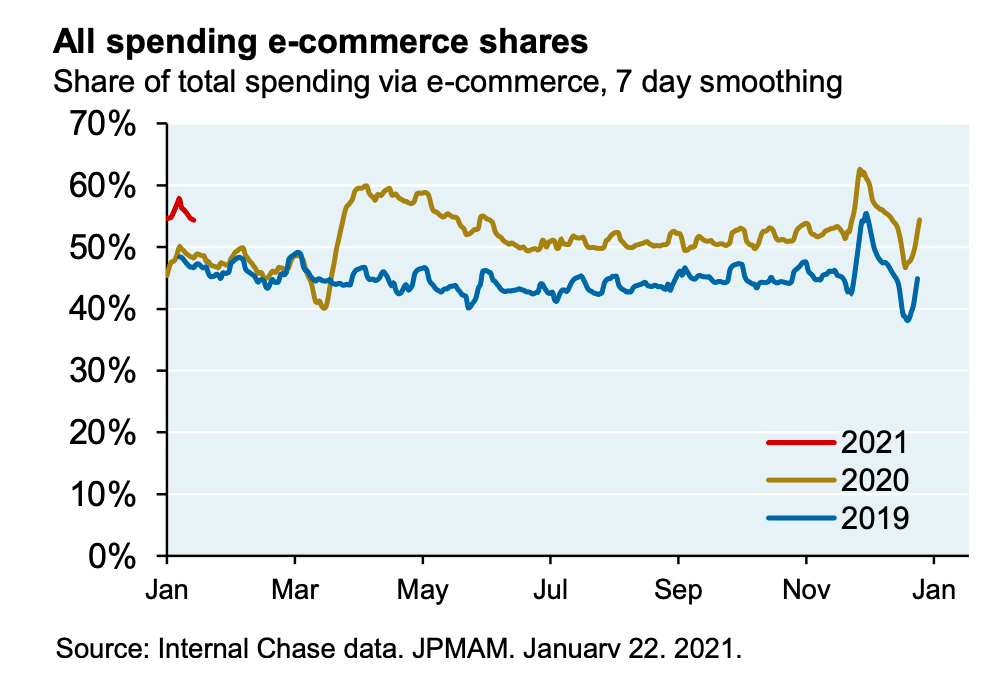

- Worth checking in with the latest recovery stats from JPM.

- This chart suggests that e-commerce continues to run at 2020 levels – will be interesting to see if this is a permanent change as the year goes on.

Benedict Evans Slide Deck

- Another fascinating must-see slide deck from Ben Evans on tech and media.

Fund Performance

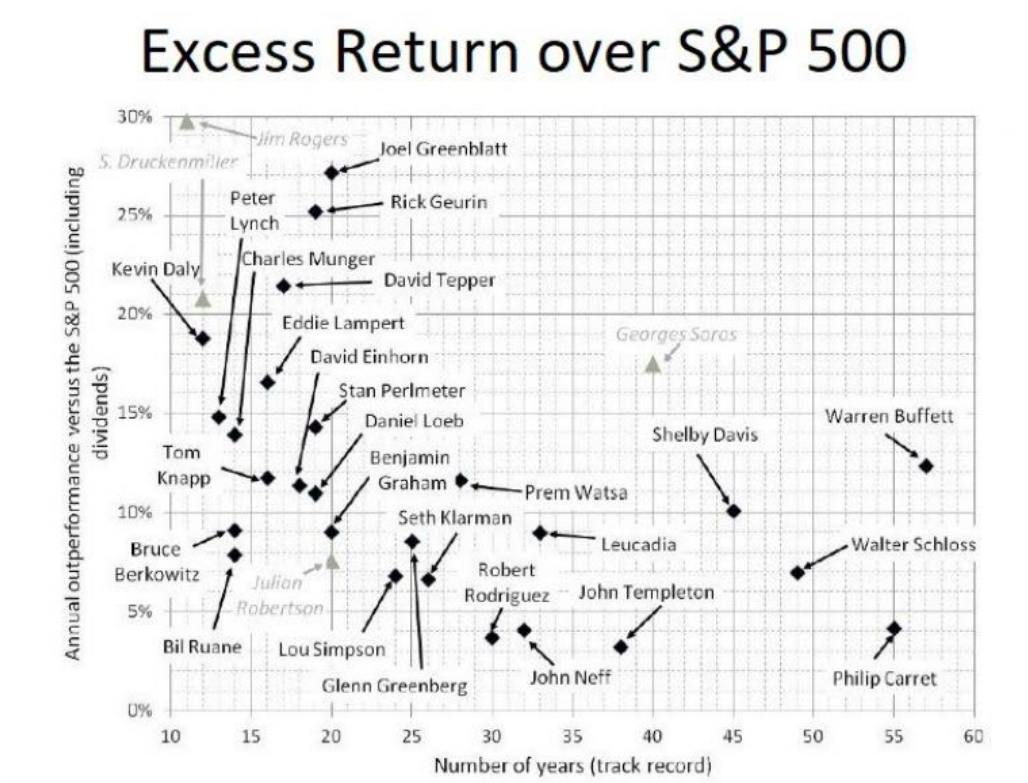

- Interesting chart plotting excess returns of various managers against the durability of this performance.

74 NYT Facts

- “Each day, our editors collect the most interesting, striking or delightful facts to appear in articles throughout the paper. Here are 74 from the past year that were the most revealing.”

- Great list from NYT. A few examples:

- “Brooks Brothers, which Henry Sands Brooks founded in Manhattan in 1818, is the oldest apparel brand in continuous operation in the United States.“

- “Often, the screams we hear in movies and TV are created by doubles and voice actors. One stock scream is so well-used it’s got a name, the Wilhelm. It’s in hundreds of films.“

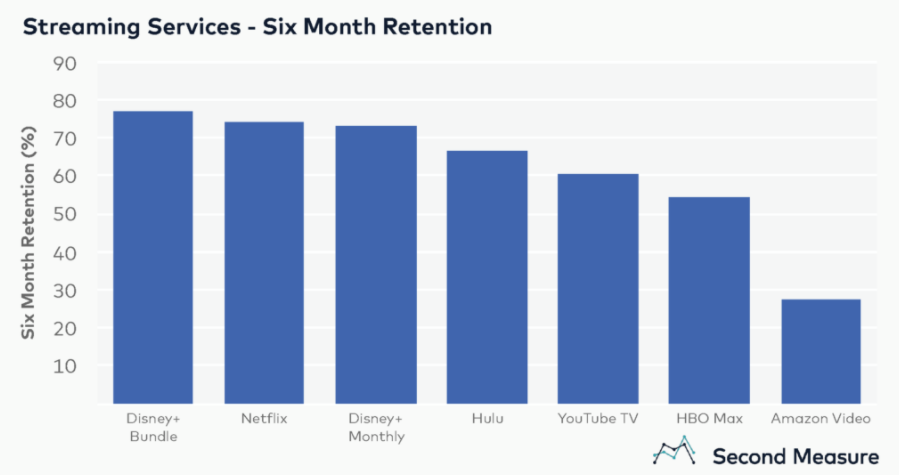

Streaming Retention

- Interesting chart showing that Disney Plus now has market leading customer retention.

Akin’s Laws of Spacecraft Design Investment Analysis

- Ever wondered what spacecraft design has to do with investment analysis? Surprisingly a lot.

- Read the fourth instalment of the Snippet Blog to find out.

Akin’s Laws of Investment Analysis

Spacecraft design is hard. Akin himself says as much when he puts bluntly, as his 33rd law, “Space is a completely unforgiving environment. If you screw up the engineering somebody dies (and there’s no partial credit because most of the analysis was right ..)“.

We recently came across Akin’s laws for spacecraft design – lessons learnt from decades of space system development followed by decades more of teaching. Reading these laws one can’t help but feel they generalise so easily – replace “design” and “spacecraft” with almost anything and the vast majority of laws apply.

Here is an attempt doing just that for investment analysis, a far safer environment.

- Investment analysis is done with numbers. Analysis without numbers is only an opinion.

- To get investment analysis right takes an infinite amount of time. This is why it’s a good idea to operate when some things are wrong.

- Investment analysis is an iterative process. The necessary number of iterations is one more than the number you have currently done. This is true at any point in time.

- Your best analysis efforts will end up useless in the final analysis. Learn to live with that disappointment.

- Miller’s law – three points determine a curve.

- In nature, the optimum is almost always in the middle somewhere. Distrust assertions that the optimum is at an extreme point.

- Not having all the information you need is never a satisfactory excuse for not starting the analysis.

- When in doubt, estimate. In an emergency, guess. But be sure to go back and clean up the mess when the real numbers come along.

- Sometimes, the fastest way to get to the end is to throw everything out and start over.

- There is never a single right solution. There are always multiple wrong ones, though.

- Analysis is based on process. There is no justification for analysing something one bit “better” than the process requirements dictate.

- (Edison’s Law) “Better” is the enemy of “good”.

- (Shea’s Law) The ability to improve analysis occurs primarily at the interfaces. This is also the prime location for screwing things up.

- The previous people who did a similar analysis did not have a direct pipeline to the wisdom of the ages. There is therefore no reason to believe their analysis over yours. There is especially no reason to present their analysis as yours.

- The fact that an analysis appears in print has no relationship to the likelihood of its being correct.

- Past experience is excellent for providing a reality check. Too much reality can doom an otherwise worthwhile investment analysis, though.

- The odds are greatly against you being immensely smarter than everyone else in the field.

- A bad piece of investment analysis with a good presentation is doomed eventually. A good piece of analysis with a bad presentation is doomed immediately.

- (Larrabee’s Law) Half of everything you hear in a classroom is crap. Education is figuring out which half is which.

- When in doubt, document.

- (Bowden’s Law) Following a testing failure of your analysis, it’s always possible to refine the analysis to show that you really had negative margins all along.

- (Montemerlo’s Law) Don’t do nuthin’ dumb.

- (Ranger’s Law) There ain’t no such thing as a free launch.

- Mo’s Law of Evolutionary Development) You can’t get to the moon by climbing successively taller trees.

- (Roosevelt’s Law of Task Planning) Do what you can, where you are, with what you have.

- (de Saint-Exupery’s Law of Design) An analyst knows that they have achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.

- Any run-of-the-mill analyst can make something which is elegant. A good analyst is efficient. A great analyst is effective.

- (Henshaw’s Law) One key to success is establishing clear lines of blame.

- (McBryan’s Law) You can’t make it better until you make it work.

- You really understand something the third time you see it (or the first time you teach it.)

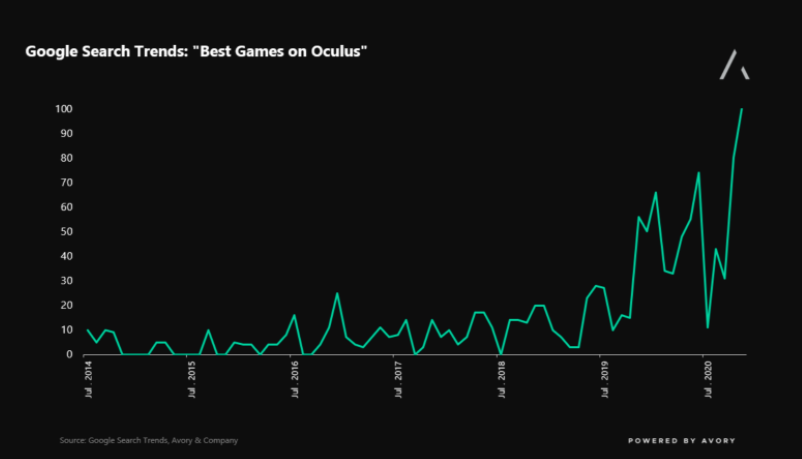

VR

- VR is taking off.

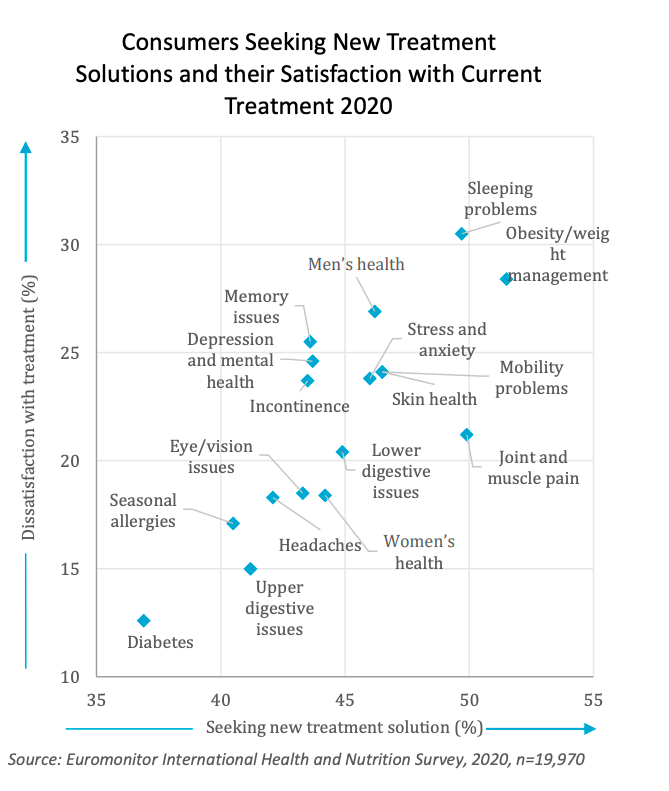

Consumer Health

- Nice chart from Euromonitor on what could be the big growth areas in consumer health.

- Euromonitor expects demand for conditions such as sleep, stress, digestion, mood/depression, memory/cognition, and weight management to surge in 2021.

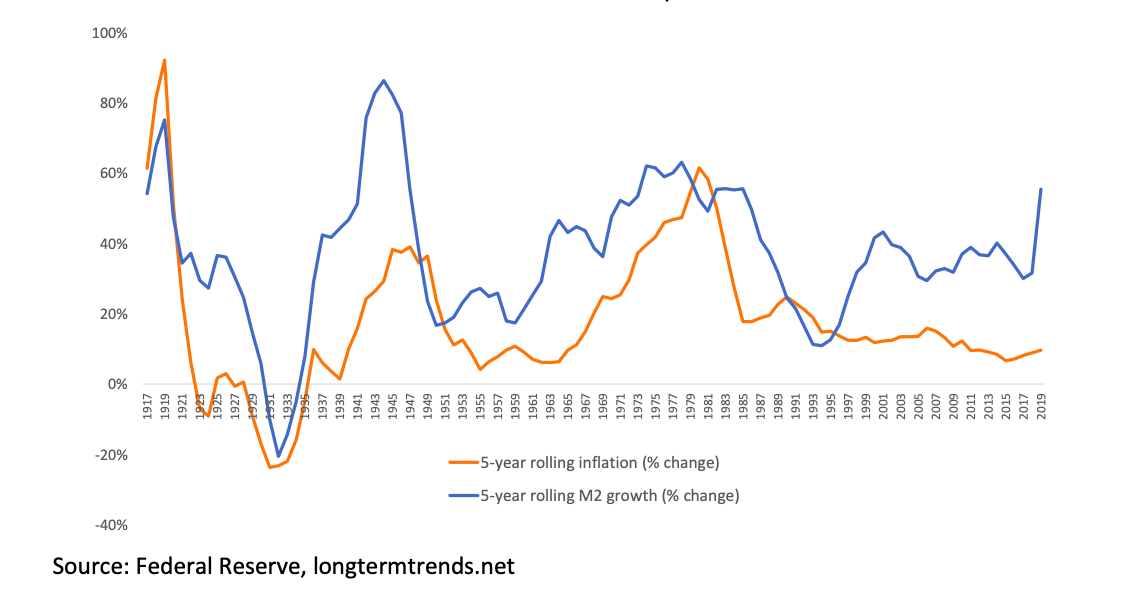

Inflation

- Could the accelerating M2 cause inflation?

FundSmith 2020 Letter

- A good read as always.

- “What are the similarities between a forecaster and a one-eyed javelin thrower? Answer: Neither is likely to be very accurate but they are typically good at keeping the attention of the audience.“

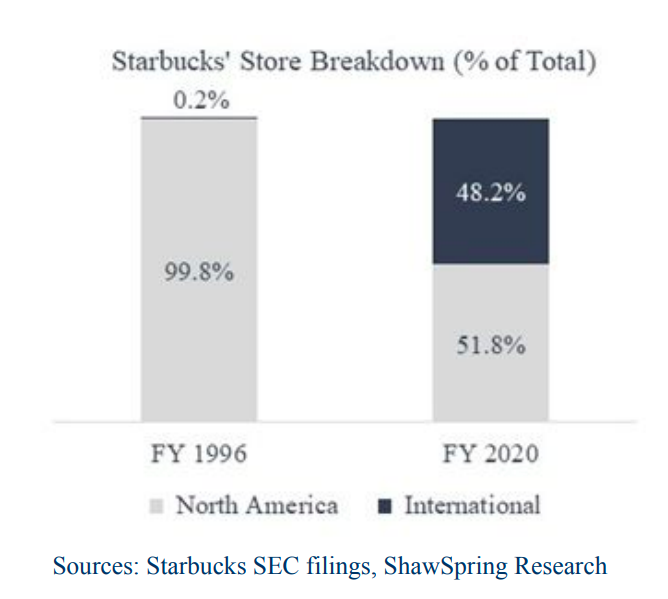

Starbucks

- It is really astounding how SBUX business has evolved from nearly 100% US focussed to a global business.