- Another wonderful list from KK (the previous one is here).

- A few of my favourites:

- Half the skill of being educated is learning what you can ignore.

- Ask funders for money, and they’ll give you advice; but ask for advice and they’ll give you money.

- It is the duty of a student to get everything out of a teacher, and the duty of a teacher to get everything out of a student.

Behavioural

The First Financial Engineer

- Robert (Bob) Merton is a giant of modern finance science.

- He is also, as argued by Andrew Lo in this really outstanding talk, the first financial engineer.

- It is in this combination – being both a scientist and engineer that his true astounding contribution surfaces.

- “I believe that a body of knowledge only becomes a science when a corresponding field of engineering emerges from it.”

Compounding

- Compounding is very difficult for human minds to comprehend.

- As the famous riddle goes:

- “Imagine it’s 10:00 AM on a small pond with a single lily pad. If the number of lily pads on the pond doubles every minute, and the entire pond is full of lily pads by 11:00 AM, at what time is the pond half full of lily pads?“

- The answer is here and many get this wrong.

- Morgen Housel brings this up in his conversation with Tim Ferriss (worth a full listen) when he talks about Warren Buffett who’s real talent, when compared to other greats like Jim Simons, was not the level of investment returns (Simons’ are much higher) but their longevity. As he says “if Buffett had retired at age 60, like a normal person might, no one would’ve ever heard of him” (transcript).

Genius

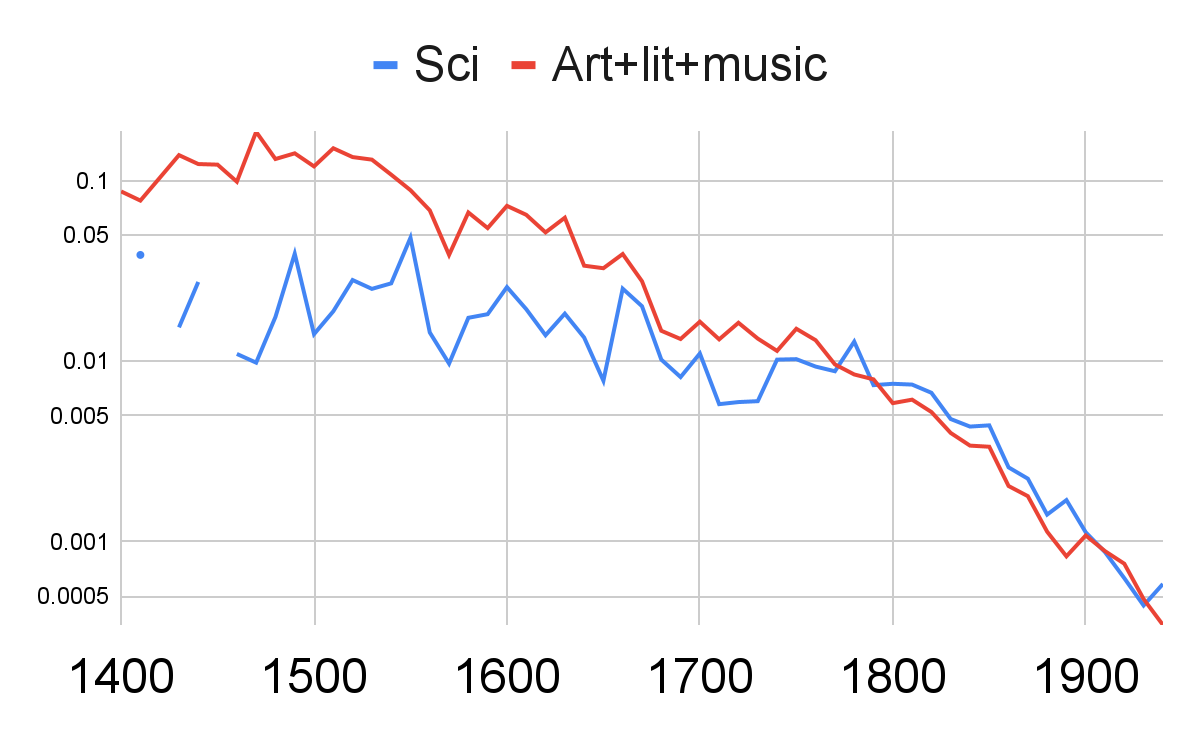

- “Below, we can see the number of acclaimed scientists (in blue) and artists (in red), divided by the effective population (total human population with the education and access to contribute to these fields).”

- Full data source. h/t Astral Codex

Are you Smart enough to work at Google?

- 10, 9, 60, 90, 70, 66 … what is the next number in this series?

- Give it a try.

- This is a question asked during an interview at Google.

- So is this one “You are shrunk to the height of a penny and thrown into a blender. Your mass is reduced so that your density is the same as usual. The blades start moving in sixty seconds. What do you do?”

- Both of these interview questions are taken from this brilliant book which is about difficult interview questions at top companies.

- Once you tried those questions – hit this preview link for the answers.

Dan Loeb

- A belated snippet of this outstanding profile of legendary investor Dan Loeb (I posted his letters several times) – founder of Third Point Capital, a $20bn hedge fund, that compounded over +15% pa for 25 years and pioneered activist investing.

- Third point is named after his favourite surf break in Malibu.

- In the early days of the fund – Loeb posted on forums as “Mr Pink”. Interesting to see further confirmation of media-first investors.

52 Things I learned – 2021 edition.

- We previously covered this brilliant list of 52 things learnt for 2018, 2019 and 2020.

- Here is the 2021 edition – full of gems. A few choice examples:

- “Social media headlines are evolving fast. Since 2017, they’ve got shorter (11 words vs 15 words), and many clickbait phrases like “…will make you…” or “things only … will understand” no longer work.” [BuzzSumo].

- “Adding nature imagery (grass, trees, rainbows) to a pitch document seems to increase the likelihood of investment a little.”

- “Baileys Irish Cream was invented in 45 minutes in 1973 by two ad creatives in Soho.“

Energetic Aliens

- What accounts for the difference between “cognitive stamina and observed levels of energy between individuals“?

- This article is a really interesting start on understanding these so-called “energetic aliens” – people who can work hard, consistently and obsessively.

- Examples include George Church who “after finishing his undergrad in 2 years, worked 100 hour weeks in the lab during grad school, famously getting kicked out due to not attending classes because he was just so absorbed in his research.“

- As well as – Napoleon, Robert Moses, Alexander Grothendieck, Paul Erdos, Isaac Asimov, Honore de Balzac, Danielle Steel and more.

- Absolutely worth a read.

The Monty Hall Problem

- 🚪🚪🚪Three doors.

- Behind one is a car 🚗. Behind the other two are goats 🐐.

- You pick a door. The gameshow host opens another, revealing a goat.

- You can choose to stay with your original choice or switch. What should you do? [Give it a try!].

- The Monty Hall problem became famous when a columnist, Marilyn vos Savant, known as the world’s smartest woman, said you should switch, resulting in hundreds of letters, including from the brightest minds in mathematics, arguing she was wrong.

- This engrossing article by Steven Pinker shines a bright light on this dilemma.

- “People’s insensitivity to this lucrative but esoteric information pinpoints the cognitive weakness at the heart of the puzzle: we confuse probability with propensity.”

- “A propensity is the disposition of an object to act in certain ways. Intuitions about propensities are a major part of our mental models of the world.“

- Probability is “the strength of one’s belief in an unknown state of affairs“

- “The dependence of probability on ethereal knowledge rather than just physical makeup helps explain why people fail at the dilemma.“

- “They intuit the propensities for the car to have ended up behind the different doors, and they know that opening a door could not have changed those propensities. But probabilities are not about the world; they’re about our ignorance of the world. New information reduces our ignorance and changes the probability.“

- Surely there is an analogy here to investing.

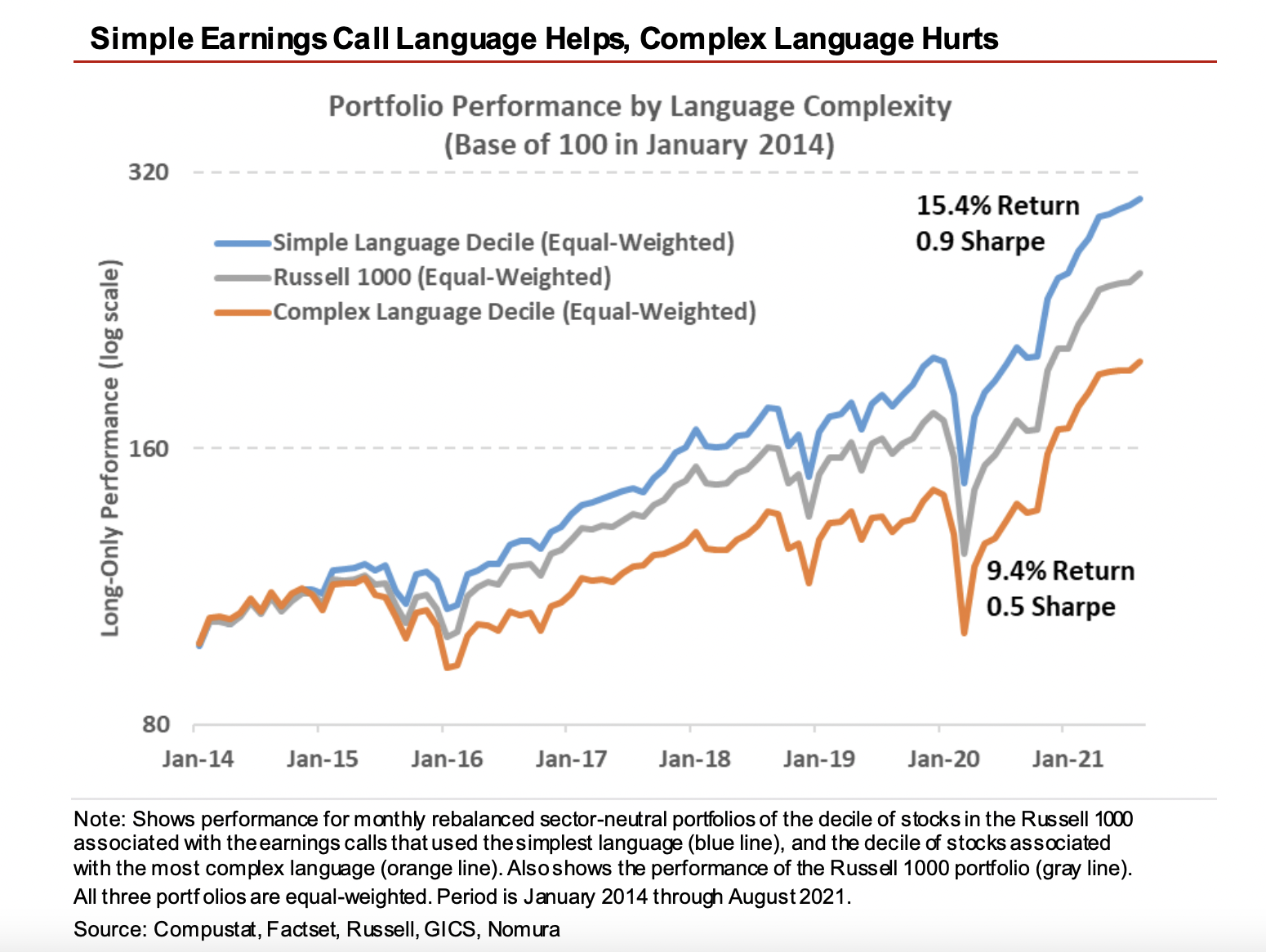

The Value of Simple Language

- The type of language used in earnings calls has a significant impact on stock returns.

- According to Nomura, simple language (as measured using Gunning Fog Index) leads to higher returns and a considerably better Sharpe ratio when compared to complex language.

- This is distinct from earnings call length – which doesn’t correlate to complexity.

- For those interested we previously posted further interesting stats on language in company publications.

Orwell on Writing

- Orwell offers a lot of advice on writing well, a vital skill for any investor, in his essay “Politics and the English Language”

- This post pulls out some of the main “bad habits” to be avoided.

- It matters because writing clearly reveals understanding.

- “You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you — even think your thoughts for you, to certain extent — and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even yourself.”

- “A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?“

AntiLibrary

- “Tsundoku (積ん読) is a beautiful Japanese word describing the habit of acquiring books but letting them pile up without reading them.“

- So starts a sublime essay on the antilibrary – “a private collection of unread books”.

- What is a digital version of that?

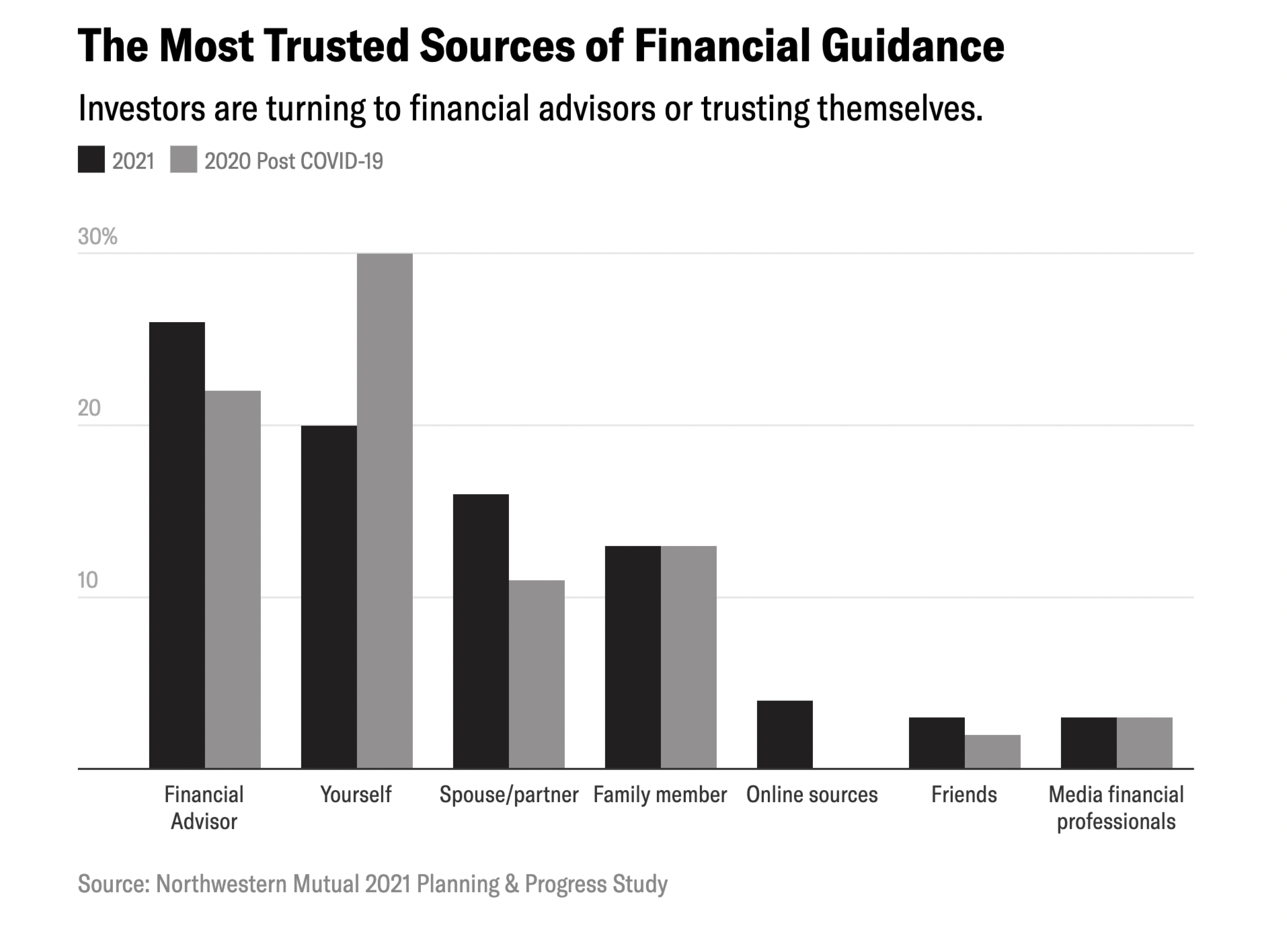

Best Source of Financial Advice

- 2,300 Americans were asked who they think the best source of financial advice is.

- Right after financial advisor, a staggering proportion said either themselves or their partner.

- Interestingly dead last, at just 3%, was financial professionals in the media.

Investing Aptitude

- “Aptitude is the rate at which you level up, by changing the nature of the problem you’re solving (and therefore how you measure “improvement”). The interesting thing is, this is not purely a function of raw prowess or innate talent, but of imagination and taste.“

- This is a nice way to think about learning in investing – as returns to a particular area diminish, it is key to open a new front.

The Hedgehog and The Fox, revisited

- Many readers will have heard of the famous distinction from the celebrated essay by Isiah Berlin.

- But few have read past the first chapter. Much of the brilliant writing has been overlooked.

- The latest Snippet Blog article is a correction of that omission.

- In Berlin’s words are ideas that give the analogy a much deeper meaning and in the process help guide investors.

The Hedgehog and The Fox, revisited.

“There is a line among the fragments of the Greek poet Archilochus which says ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing’“.

Thus starts one of the most celebrate essays of Isiah Berlin, first given as a lecture at Oxford, then written down and buried in an obscure journal before being resurrected, extended and published. It was an instant hit and to this day is Berlin’s most popular work.

The popularity of the work stems almost entirely from the distinction captured in that first line that “marks one of the deepest differences which divides writers and thinkers, and, it may be, human beings in general“. From its first appearance in 1953, this distinction captured the imagination of the Western world, largely because of its simple and powerful intuition. Everywhere commentators were separating people into hedgehogs, who “relate everything to a single central vision, one system … a single, universal, organising principle“, and foxes, who “pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way … related to no moral or aesthetic principle.”

This categorisation, between monists and pluralists, reached the shores of the investing world at the turn of this century (from what I can tell). It was given a big push by the popularity in those circles of the 2005 book Superforecasting by political scientist Philip E. Tetlock. Tetlock borrowed the analogy heavily as a way to support the key finding of the Good Judgement Project – that foxes (generalists, realists) were better forecasters than hedgehogs (experts, specialists). Forecasting, after all, is crucial for investing. Today a Google Search of “investing hedgehog fox” yields 945,000 results – blog posts, articles and even a book – and none of the results involve erinaceous or vulpine ETFs.

I recently re-read the original essay. It is a master class in writing. Sentences span whole paragraphs and yet have the clarity of an alpine lake. Arguments are beaten home to the drum of nuanced repetition. What is astounding though is that Berlin only dwells on the famous analogy for a mere three pages. The thrust of the essay is dedicated to understanding Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy, who, Berlin hypotheses, was “by nature a fox, but believed in being a hedgehog“. This conflict is dissected on the plate of Tolstoy’s view of history, itself dismissed by critics and ignored by readers.

As I made my way through this essay it dawned on me that many of the commentators in the investment world (and more widely) had very likely never read past the first chapter. Much like Tolstoy’s philosophy of history, the bulk of The Hedgehog and the Fox, has “not obtained the attention it deserves“. This post is a correction of this omission. Like the fox, I don’t seek to construct a unified theory, but rather pull-out interesting observations, as they relate to investing. Ideas that Berlin clearly intended to help us move beyond the surface level of the analogy, thereby deepening its meaning and usefulness.

Investors are actually foxes that want to be hedgehogs

The premise of Berlin’s essay is that Tolstoy was a fox but wanted to be a hedgehog. It strikes me that investors, the good ones at least, are all in fact exactly like this.

Foxes are good at pointing out flaws in other’s theories (especially those of hedgehogs). Tolstoy was in this respect perhaps the fox. At his hand “pretenders are exposed and struck down one by one” with an intellectual force never seen before (or since). A good investor must posses this quintessential fox’s quality, the ability to take down other’s ideas.

In Tolstoy’s ideas on history we can see this process at work. He strongly rejected the scientific approach to history. There are no dependable laws to be discovered, no underlying causes and hence predictions are impossible. Historians who attempt this, commit “a gross error” by setting emphasis in a world where determinants are vast and varied and, consequently, no one individual, no matter how powerful, can guide destinies.

Yet all this intellectual chipping isn’t destruction – it has a purpose. Tolstoy believed stronger than anyone else that a core exists, the answer is out there. He wanted to be a hedgehog. Yet, this can only be achieved if one walked the path of the fox. Precisely in taking down his opponents the answer might eventually reveal itself. “He continued to kill his rival’s rickety constructions with cold contempt, as being unworthy of intelligent men, always hoping that the desperately-sought-for ‘real’ unity would presently emerge from the destruction of the shams and frauds“. A good investor embodies this – they are compelled by a sense that the truth is out there, although they can’t grasp it. The path to that truth is argument. Like a sculptor who starts with a sheer slab of stone, every chip brings one closer to the truth.

Does the essay give any clue what the truth might be?

History, in Tolstoy’s eyes, is only a blank succession of unexplained events, an “inexorable process”, “a thick, opaque, inextricably complex web of events, objects, characteristics, connected and divided by literally innumerable unidentifiable links – and gaps and sudden discontinuities too, visible and invisible“. One could just as easily use this description for the march of financial markets.

Tolstoy believed those who fail to face the “inexorable historical determinism” miss the most important thing – the “inner events“, “the most real, the most immediate experience of human beings“. In elevating history to political and public events, individuals are blurred. There is stark contrast between “real life – the actual, everyday, ‘live’ experience of individuals with the panoramic view conjured up by historians“. This is ironic because “no one in the actual heat of the battle can begin to tell what is going on” – something Tolstoy makes clear time and time again in his great historic novel War and Peace.

So to understand what is going on around us we must look to the indivisible units – human beings. This is something all great investors know – that companies and markets consists of people. In order to piece together history, and the markets, these units must be integrated. How? “This is the integrating of infinitesimals, not, of course, by scientific but by ‘artisitic-psychological means‘”. In other words, some of the answer lies in understanding human psychology. It is not that we must wholly reject scientific approaches but that we must give the ‘inner’ world equal prominence as the ‘outer’. Tolstoy’s preferred tool here was the novel, and it does beg the question why more novels exploring the inner lives of ordinary workers, market participants or consumers aren’t written.

What makes this integration so difficult is that we simultaneously live inside it. The very tools we use to understand the world, are what we are trying to understand. “Our thoughts, the terms in which they occur, the symbols themselves, are what they are, are themselves determined by the actual structure of our worlds”. Investors live inside the market they are trying to conquer.

Berlin offers some advice here – “for we ourselves live in this whole and by it and are wise only in the measure to which we make our peace with it“. In short, investors must come to terms with their own psychology. This reminds me of another beautiful quote by Huxley “We cannot reason ourselves out of our basic irrationality. All we can do is to learn the art of being irrational in a reasonable way.“

By reading past the title and the first few pages, readers are rewarded with a much deeper understanding that can be carried over to other domains. A fox who wants to be a hedgehog is a more appropriate characterisation of a good investor than the oft drawn distinction between the two animals. It is better to argue one’s way to the truth, than to try to construct it. In the same way, even Tolstoy’s own theory of history holds lessons for investors – to look past the panoramic view and focus instead on the indivisible units – human beings. It is in understanding human psychology, including one’s own, that some of the mysteries of markets can be unlocked.

All is not rosy though. A fox that dreams of being a hedgehog, is a tormented existence. The stronger the instinct of the fox, the stronger the desire to be a hedgehog. Berlin captures this right at the end where he describes the great thinker, and one can’t help but feel the great investor as well, as:

“at once, … omniscient and doubting everything, cold and violently passionate, contemptuous and self-abasing, tormented and detached”.

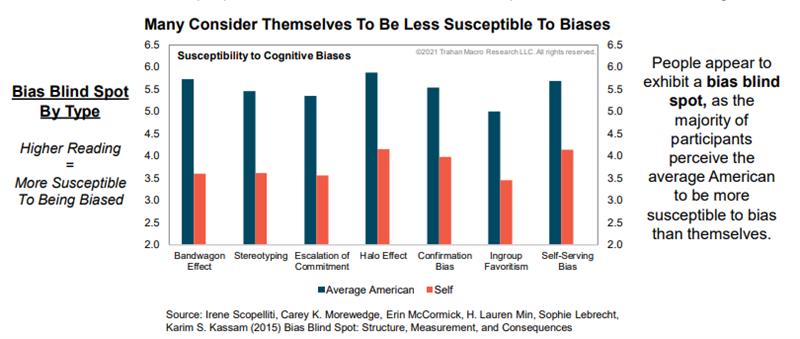

Bias Blind Spot

- “People exhibit a bias blind spot: they are less likely to detect bias in themselves than in others.“

- “Most people recognise that other people are likely to be biased when judging an attractive person, for example, but think that their own judgment of an attractive person is unaffected by this type of halo effect.“

- Clearly, the majority of people cannot be less biased than their peers – hence the blindspot.

- Source.

Psychology of Human Misjudgement

- An investing classic – must read talk by Charlie Munger – rewritten in 2005.

- In it he covers 25 biases that all investors should know.

Luck

- How to make your own luck. Lots of interesting ideas inside re biases and the “serendipitous mindset”.

- Key elements are being “open and alert to the unexpected” and being “prepared”.

Being Negative

- This is an eye-opening essay on The Art of Negativity with useful read-across to investing.

- This was an interesting result from research – “there is a clear “asymmetry in the way that adults use positive versus negative information to make sense of their world; specifically, across an array of psychological situations and tasks, adults display a negativity bias, or the propensity to attend to, learn from, and use negative information far more than positive information.“”

- A nice quote – “An optimist believes we live in the best possible of worlds. A pessimist fears that this is true.”